How Alex Lyon’s survival instincts brought him to Buffalo

Buffalo Sabres goalie Alex Lyon is in his 10th NHL season, on a path that started in the northernmost reaches of Minnesota, went through the Midwest, Yale and then the American Hockey League.

Alex Lyon compares his career as a professional hockey player to that of a cockroach.

Bear with the Buffalo Sabres goalie. He’s the cerebral type.

Sabres goaltender Alex Lyon makes a save in the second period against the Maple Leafs on Oct. 24 at KeyBank Center.

Joed Viera, Buffalo News

Lyon has seen every angle of hockey at every level. He’s been part of a team in a community school, where in a senior class with 25 boys, 24 played sports to fill a roster.

He won a championship in the American Hockey League and helped launch a current NHL juggernaut in Florida.

He has been promoted to the NHL, multiple times. Demoted to the AHL, multiple times. Worked in backup roles and starting roles. Questioned his future and his present, many times over, in the course of his first nine seasons as a pro. At times, he’s even thought, “I can leave it all behind and fall back on my education from an Ivy League university.”

His survival instinct kicks in each time. Cockroaches survive almost anything.

They change as the world changes. They can regenerate their own limbs. They can survive radiation, starvation and extreme conditions. They aren’t just household pests. They are critical to the ecosystem's progression.

“It’s about sticking around and working hard,” Lyon said. “There’s no secret to success. Staying healthy is extremely important, as well. Luck plays a factor. But it’s like any other job. No secrets. No shortcuts.”

Lyon doesn’t necessarily have super-human abilities. What he has is the ability to adapt, to learn, to shed old habits and create new ones.

Lyon is a one-time journeyman who signed with the Sabres in July, with the expectation of backing up Ukko-Pekka Luukkonen. The hope? Luukkonen, the Sabres’ incumbent No. 1 goalie, would regain his consistency after an up-and-down 2024-25 season.

Instead, Lyon started 10 of the Sabres’ first 13 games as Luukkonen recovered from lower-body injuries that kept him out of much of training camp and the first two weeks of the season. Lyon is part of a stable that has given the Sabres a unique problem at the position: How do they use Luukkonen’s experience, Colten Ellis’ possibilities and youth and Lyon’s ability to step into any situation?

“Every year, you look and Alex seems to have a net someplace,” said Bliss Littler, Lyon’s coach with the Omaha Lancers of the United States Hockey League. “He’s a social climber. He continues to impress the people he’s playing for in each organization he plays in.”

Being resourceful

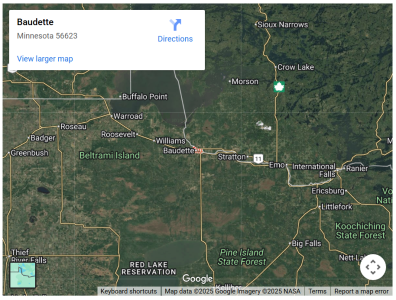

Lyon’s ability to survive and evolve comes from the can-do attitude he gained from growing up in Minnesota’s northernmost reaches. He learned the values of equanimity and composure, focusing on solutions and being self-reliant while being practical and educated.To understand Lyon, 32, is to learn where he comes from. Baudette, Minn., is a town of fewer than 1,000 people, about 13 miles from the south shore of Lake of the Woods. The lake is tucked into a corner between the border of southeastern Manitoba and upper western Ontario.

Lyon’s local school, Lake of the Woods, has a kindergarten through 12th-grade enrollment of less than 460 students. His older sister, Samantha, is the school’s activities and community education director, but she’s a jack of all trades. The school’s website lists her roles as the college and career readiness coordinator and the junior high softball coach.

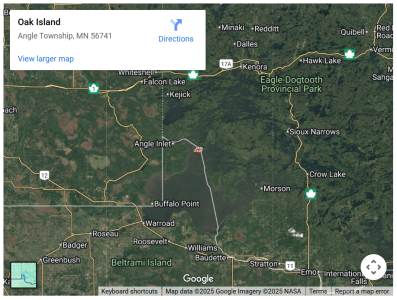

The Lyons live in a community where everyone has to pitch in to make things operate, whether it was driving the Zamboni at the local hockey rink or even making ketchup from scratch. Samantha Lyon recalls how her family ran a fishing resort on Oak Island, on Lake of the Woods’ northern maritime border with Canada.

Much like a team, every person in the family and within the resort had a role they needed to fill so that the resort could be self-sustaining. If the kitchen ran out of ketchup, there was no way to just go to the grocery store or the Costco up the street and buy an industrial-sized jug of the condiment.

The Lyons had to figure out, quickly, how to make ketchup.

“You’ve heard Alex talk a lot about his work ethic, and both of us have inherited that from our parents,” Samantha said of her father, Tim, and mother, Deb. “I talk about it as a resourcefulness. We might not have all the information at our fingertips, but we work hard and make ourselves learn the process and figure out how to do it.”

Panthers goaltender Alex Lyon stops a shot by Sabres right winger Alex Tuch during the second period of the Panthers' 2-1 win on April 4, 2023, in Sunrise, Fla.

Associated Press

One call away

Lyon was a junior in high school when he realized he could play college hockey.“Division III college hockey,” he clarified. “Get a good education.”

He didn’t set his sights too high, but the following year, as a senior in 2010-11, he won the Frank Brimsek Award as the top high school goalie in Minnesota.

He still didn’t have thoughts of professional hockey. Lyon’s approach was, what will it take for me to get to the next level, and what do I need to do to succeed there?

Keith Allain coached the Yale men’s hockey team from 2006-25 and learned of Lyon through a phone message from Lyon’s grandfather, Pro. Lyon’s parents, grandfather and great grandfather are Yale graduates, and like any family member, Lyon’s grandfather advocated for his grandson.

The funny thing about it?

“I had a voicemail on my landline, and I don’t listen to that very often,” Allain said. “Alex’s grandfather is telling us about this great goaltender and his grandson in Baudette, Minnesota. I get a lot of calls like that, but I had my assistant make a phone call or two, and he told me, ‘I think the kid’s pretty good.’ ”

That assistant coach? Dan Muse, who is now in his first season as head coach of the Pittsburgh Penguins.

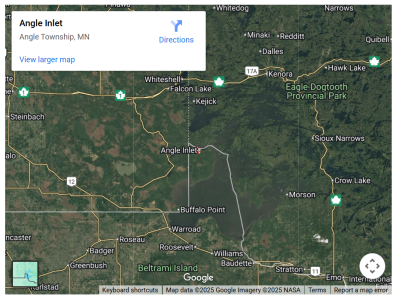

Muse traveled to the the Northwest Angle, the northernmost contiguous point in the Lower 48 United States and an American exclave, to scout Lyon.

Heading to Yale, though, required Lyon to take a detour through the Great Plains, first to Iowa, and then to Nebraska.

From Cedar Rapids to Omaha

The Cedar Rapids RoughRiders had a glut of goaltenders in the fall of 2011. The Omaha Lancers didn’t have enough experience in the net. Littler, who coached the Lancers at the time, recalls a phone conversation he had with Mark Carlson, the longtime Cedar Rapids coach.“Their coach told me, ‘I need to get this kid to a place where he’s going to start, and you guys have a good team, but no starting goalie,’ ” Littler said. “Playing in Cedar Rapids, they had two or three goalies who were good enough to be starters."

Littler weighed the possibility of a trade, for a moment, and Carlson and Littler agreed on trading Lyon to Omaha for a seventh-round pick in a future USHL draft.

Littler said Carlson added one thing before they hung up:

“In the end, I’m doing you a favor. I need to do the right thing for a player and get him a starting position,” Carlson told Littler.

Lyon supplanted a goalie named Thatcher Demko – now with the Vancouver Canucks – who, at 15 years old, wasn’t ready for the grind of a 60-plus-game USHL schedule. Lyon, Littler said, was “the guy, right away.”

Lyon had already committed to Yale by the time he entered the USHL, one of the major proving grounds for Division I college hockey prospects. He shined in Omaha.

He made the USHL All-Rookie team in 2011-12, going 28-15-3 with a 2.76 goals-against average and a .910 save percentage and four shutouts in 48 games.

The next season, he was 26-21-1 with a 2.65 goals-against average, a .916 save percentage and one shutout. He was a second-team All-USHL selection.

“He needed an opportunity to be the guy,” said Littler, who is now general manager of the Wenatchee Wild of the Western Hockey League. “Junior hockey is something for goaltenders where they need to get a net and an opportunity, and they need to play a lot. Goaltenders in junior hockey hope to get into the net, early enough.”

Yale goalie Alex Lyon is shown during the first period of an NCAA game against Michigan Tech on Jan. 10, 2016, in Glendale, Ariz.

Rick Scuteri, AP file

'This is great, I'm at Yale'

Lyon joined the Yale hockey team as a 20-year-old freshman in the fall of 2013. Allain described Lyon as someone who “wasn’t quite sure where he fit in, in the hockey world.”He still wasn’t thinking about professional hockey. He thought more about the future in terms of how Yale could help him.

“I went to school and I was like, ‘This is great, I’m at Yale, I’m going to get a great job,’ ” Lyon said.

Then, Lyon started playing well. NHL scouts came calling. And visiting New Haven, Conn. And hounding Yale hockey. It introduced Lyon to a new form of recruiting.

“It became a little bit of a sideshow,” Allain said.

Allain and Lyon formulated a plan for Lyon’s future at the start of his junior year. Make a decision by Christmas of 2015, if you want to stay for a fourth year at Yale or turn pro. He had to decide what was the right thing to do, and if or when it was the right time to make a move to start his professional career.

He signed with the Philadelphia Flyers as a free agent in April 2016 after three years with the Bulldogs and two All-American seasons. In 93 games from 2013-16 at Yale, Lyon was 50-29-14, had a .931 save percentage, a 1.89 goals against average, 15 shutouts and helped the Bulldogs to NCAA Tournament berths in 2015-16.

Lyon became the first Yale hockey player in more than 10 years to leave the Bulldogs before his eligibility expired.

“I was convinced that when we had Alex at Yale, that he was an NHL goalie,” Allain said.

Up and down, still around

So much of the glory Lyon gained in the USHL and in college meant little once he was a pro. He played for Lehigh Valley of the AHL for his first two years of professional hockey. He split his first seven seasons between the NHL and AHL with Philadelphia, Carolina and Florida, and didn’t play a full season with an NHL team until he played 44 games with Detroit in 2023-24.He still had it in the back of his mind that he had his Yale education as a fallback plan. There were moments when he wondered if this was it. If someone was going to step on the cockroach and end its chances at surviving another cataclysmic event.

“A lot!” Lyon exclaimed, laughing. “I always joke about that on bad days. But I think, literally, every professional athlete is like, and I’m always like, ‘I gotta go see where my degree is at, I might need it.’ But it’s the nature of being a professional athlete. It’s such a fleeting existence, and I feel really lucky.

“I hate to use the word ‘blessed,’ but I do feel that way about being in this position, and I try not to take it for granted. I wish I had a definitive thing that I lived by, but you have to adjust. I don’t even think you have to adjust your game as much as your mentality. This is my fifth (NHL) team, and every team is something different. You have to fit in with the team.”

He draws another analogy, this one from martial arts and film icon Bruce Lee, who held a philosophy: Adjust to the circumstances and form yourself to the surroundings.

“You have to be like water,” Lyon said.

That came whether it was in the spring of 2022, when he helped Chicago win the American Hockey League championship, or in April 2023, when he made 39 saves to lift Florida to a 2-1 win against the Sabres in Sunrise, Fla. That win ultimately helped the Panthers earn the final Eastern Conference wild-card playoff berth, as they finished one point ahead of the Sabres and Penguins in the final regular-season standings.

Lyon’s win also helped the Panthers reach the first of three Stanley Cup Finals; the Vegas Golden Knights defeated the Panthers to win the NHL championship.

In 125 NHL games prior to Friday, Lyon is 54-43-14 with a .903 save percentage, a 2.99 goals-against average and five shutouts. He is 3-5-3 in 12 games with the Sabres, with a .907 save percentage and a 3.07 goals-against average entering Friday’s game against Chicago.

Discipline, Samantha Lyon said, has driven her younger brother. Creating and maintaining a consistent work ethic that never wavered. Understanding when he felt strong or felt tired, or if his reactions were a fraction of a second ahead of or behind the pace of the game.

What can I do to maintain this? Or improve this?

“The part of his story that I continue to be amazed by is that he was undrafted,” Samantha Lyon said. “Not only has he created a strong, long career for himself, but he did it out of nowhere. He just kept chipping away at the next level. You’ll hear my parents talk, and they’ll say, ‘We never had any expectations of where he will go.’ But it was, ‘He is getting opportunities at the next level and we will do whatever we can to help him get to the next level.’ He kept plugging away at what was needed to be successful.”Lyon has survived, and unlike what a cockroach has done to endure, he didn’t need to lose limbs, endure a radioactive environment or avoid the thwack of a newspaper about come down and crush his existence.

Lyon simply needed to find a means to work through, adjust to, survive or thrive every situation he has entered.

“I never thought I would get this far, ever,” Lyon said.