What makes Bills Mafia like no other? It's the people – and yes, it's those near-misses

Whether it’s a packed Highmark Stadium during a lake-effect blizzard or the defensive, borderline aggressive stances fans take on social media defending their players (Buffalo hasn’t forgotten Stevie Johnson), there is something unique about the fan base.

Just off Hertel Avenue, block parties and yard games line the streets.

It’s Independence Day, and Buffalo natives are spending time with their closest mates, tossing beanbags and downing hot dogs into the night. Those are pretty typical July 4 pastimes across the United States. But the camaraderie is distinct at first sight.

So, suddenly, a mother and son, clad in Buffalo Bills gear, walk across Norwalk Avenue toward a seemingly empty house. No cars in the driveway, occupants likely celebrating somewhere else. But they ring the doorbell nevertheless, holding a plate of pizza rolls and wings, and stand patiently for a solid three minutes.

“We’ll come back sometime tomorrow,” the mother says. “I’d love to meet them.”

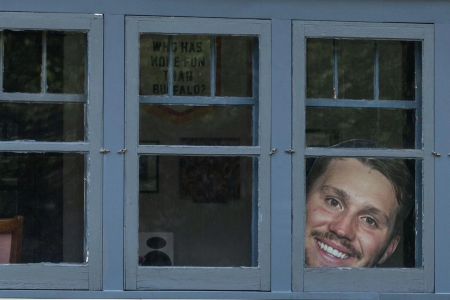

And they stroll away, leaving the house exactly as they found it – continuing to draw attention. There were 14 other intrigued visitors that evening, all but two bearing food. With a certain Bills quarterback’s face plastered across her front window, the stream doesn’t dry up for Mina Cairns.

A Fathead of Josh Allen can be seen in the front window of Mina Cairns’ home on July 30 on Norwalk Avenue.

Sophia Buonpane, Buffalo News

“Josh (Allen) gets a lot of attention, rightfully,” the 31-year-old lifelong Buffalo resident said. “And people from around here aren’t hesitant to come up to one another. … But I think that’s what makes Buffalo so special. We’ve all been shaped by the Bills. The team has determined who we are and how we interact. So, yeah, people love to talk because they care.”

It’s not unknown that those in Buffalo love the Bills. Whether it’s a packed Highmark Stadium during a lake-effect blizzard or the defensive, borderline aggressive stances fans take on social media defending their players (Buffalo hasn’t forgotten Stevie Johnson), there is something unique about the fan base. But because the world seeks balance, there are also the tailgaters launching through tables and borderline belligerent fans drinking to their heart’s desire, defining why Buffalo can party harder than anywhere else.

It’s an amalgamation of fervor, unrivaled by any other American sports franchise.

So we set out, inspired by Cairns, to determine where the passion comes from.

There were discussions about the stark weather, politics and a secluded wing-mastering metropolis. Between fans, historians, players and even psychiatrists, an unexpected source shined through.

This is how losing has morphed Buffalo into a caring, tightly knit ecosystem. One that thinks it has finally reached the culmination of its suffering, prepared to boil over at any moment.

“This is the year,” Cairns said. “This city has been living for this team.”

Bills fans celebrate a touchdown during the second quarter of a game against the 49ers on Oct. 16, 2016, in Orchard Park.

Buffalo News file photo

The collapses

The 1990s was a decade of highs and lows, Tee Forton, 62, remembers well. But similar to most other Buffalo citizens, she was all-in, no matter where the Bills went.So in 1990, as Jim Kelly’s career was blossoming, Forton found herself a job that combined everything she loved: Buffalo and the Bills. She became Kelly’s glorified secretary, organizing public events for him. And when the Bills went to their first Super Bowl in 1991, a youthful Forton thought it’d be the moment of her life. When else would you get to travel with an NFL team to a Super Bowl it was heavily favored to win? The afterparty would last for days, and it was her job to plan it to ... well, to a “Tee.”

So as she got caterers lined up and found the trendiest pad in Tampa, Fla., site of Super Bowl XXV, it never crossed her mind that the booze may never flow. Until Kelly didn’t win.

The following moments, even years, don’t need to be recounted. Four Super Bowls, accompanied by a buffet of collapses. But the first stings the most for Forton. It serves as a representation of what could’ve been.

“I still think about it all the time,” she said. “You don’t get that feeling anywhere else of just a pure, heartbreaking loss outside of here in Buffalo.”

Examining the Bills’ history, it’s not just the Super Bowls that stick out. There is the 17-year playoff drought from 2000-16, tied for the fifth-longest in NFL history. More recently, an 0-4 record versus the Kansas City Chiefs in the playoffs since 2021 dominates narratives.

For many in Buffalo, the Bills’ new rivalry with the Chiefs is just the newest in a long line of inexplicable tortures. They get so close, just to meet the same, cruel ending time and time again.

The question is: How does continuous loss shape someone? Well, that’s typically more fit for athletes to answer than those watching.

When Mickey Duzyj isn’t winning awards for the documentaries he produces or serving as a guest on “Pablo Torre Finds Out,” a popular investigative sports show, he seeks intriguing, offbeat stories. That’s where his vision for the Netflix docuseries “LOSERS” generated, weaving through tales of athlete failures and what they took from them. It struck a personal note for Duzyj.

“ ‘Victory forevermore!’ Unfortunately, that’s not how life works,” Duzyj said. “The sooner you grapple, sooner you can be happy. … I learned early that you need to define success and failure for yourself.”

Sports, unlike most other sectors of life, create a platform in which everything is defined purely by what physically occurs, at least from the outside looking in. But amid his project, Duzyj claims to have found something significantly deeper.

Defeat is rattling – Kelly surely wasn’t going to celebrate after losing to the Cowboys in ’94. However, the concept of failure can shape and cultivate new, better-developed mindsets. Athletes that struggled to get over a perceived hump, ones that “perpetually existed in second place,” believe it helped them find peace in other portions of their lives in a way most don’t.

“People who make it through failures and losses have greater wisdom,” Duzyj said, explaining that his interviewees all believe their defeats allowed them to value everything else around them, away from sports, more. “They’re forced to confront the imperfection of life. These same feelings extend in so many other walks of life. … It prepares you better than if everything just always worked out.”

He thinks that doesn’t necessarily just apply to athletes or athletics. “LOSERS” was nominated for an Emmy. Naturally, it did not win. But when it was announced, one of the athletes he worked with called him, telling him it was a victory to purely tell their stories.

Further, the group of “losers” he selected, who didn’t know one another before the project, keep in touch to this day. They share life stories, bonded by the same informative experiences.

His experience watching them, away from sports, is why he believes failure can have similar effects on fans – shaping their perspectives on life while fusing them to one another. There’s nowhere that’s more recognizable than Buffalo. And he’s not alone in the thought.

Bills fans cheer while tailgating outside Highmark Stadium on Dec. 29, 2024.

Joshua Bessex, Buffalo News

The science

Two decades ago, it would’ve been foolhardy to suggest the testosterone-infused confines of athletics, especially football, were a place where being transparent served a benefit. But now, every NFL team has a sports psychologist. They help with anything including athlete focus, ability to channel aggression into motivation and, on the unfathomable occasion a player or team loses, the ability to turn failure into a cathartic current.“Losing can be motivational, therapeutic and transformational,” said Brad Donohue, a psychology professor at UNLV who specializes in athlete mental health. He was one of eight sports psychologists who agreed that while less jarring than what athletes experience, anyone who’s emotionally tied to a result can be molded by failure. “It’s not out of the realm of possibility that Buffalo fans are truly closer to one another and kinder because they’ve all suffered together.”

There isn’t a way to statistically quantify this, but the thought is that if one cares about something to the extent it plays a significant role in their life, loss or emotional distress can alter their makeup.

The checklist, for Donohue and others, is clear, then, for Buffalo. Do Bills fans care? Enough to break their spines diving through tables. Does their fandom alter their lives? You can’t walk into a restaurant in gear without hearing a “Go Bills!”

How do they respond after a loss? By coming back again next week.

So while the city of Buffalo isn’t directly involved in any Bills loss, there’s a distinct connection between how the Bills perform and the way the city operates. That comes in two forms.

The losing, similar to what Duzyj saw in the athletes with whom he worked, unites people. You could call it trauma-bonding, but when Patrick Mahomes guides the Chiefs to a stunning victory, Bills fans clutch onto one another. Similarly, Donohue thinks “losers” can develop greater social skills.

“It can make you more understanding of others,” he said. “It helps with perspective, being able to separate from other pieces of your life and see humanity for what it is.”

What is that?

“Fractured,” he quipped, “but always trying to help itself.”

A fan holds up a Josh Allen flag during a preseason game Aug. 9 at Highmark Stadium.

Joshua Bessex, Buffalo News

The togetherness

When the NFL announced that it would expand to a 17-game schedule, Forton was happy. Not because she gets to watch the Bills for one more week each year. No, no. Because she’d get to take another family around Buffalo every other year.Forton is a lifelong Western New Yorker. Beyond the Green Bay Packers – a professional sports abnormality in that they are publicly owned – the Bills are the smallest-market NFL team. Their fans, similarly, are different.

Before 2020, Buffalo hadn’t grown for more than 70 years, according to the United States Census Bureau. It isn’t frequent you see a new face at Bills games, which is partially why the community has become as close as it has. Bills fans grow up that way, more than 30 Bills Mafia members said. There are few bandwagoners.

But Forton wants to change that.

“Every year, I like to find families or people that are visiting and then show them around the city, take them to our tailgate,” she said. The Bills are an avenue that I can share what our city is really about, and that’s what we’re caring about.”

She isn’t alone in the thought.

Buffalo’s philanthropic efforts are well-known. Bills Mafia regularly chooses charities that it partners with, raising money throughout the year. When opposing teams come to town, the fan base frequently floods enemy players’ organizations with aid. And that’s just skimming the surface of their work.

“The fact that Buffalo Bills fans – one of the most tortured of all pro sports’ fan bases – is synonymous with the greatest charitable force in pro sports,” Duzyj said, “absolutely does not feel like a coincidence.”

It draws from a history of coming up just short. But it all could change soon.

The promise

Cairns doesn’t think people will stop coming up to her house if the Bills win the Super Bowl. If anything, it’ll occur more.She can envision the celebration, with fans leaving their houses in celebration in the surely frigid streets of Buffalo. It all feels so close to ending.

With the Bills entering a season where they’re expected to be among the Super Bowl front-runners, there’s a glow around Buffalo that this may be the year. That those decades of torture and failure, which have pulled the community together and created a genuinely caring environment, may finally reach a conclusion.

“I think being on the (cusp), it definitely creates a huge bond,” Forton said. “We’re all cut from the same mold. We’ve all weathered the same things.

“Now, if we win, we’re all going to do it together. And I wouldn’t want to have done it any other way.”